A Trial Kanban Project – What Worked. What Didn’t.

Recently I introduced Kanban to an inflight development project with the objective of trialling this technique with the team to raise productivity by overcoming various communication and process issues. In the first part of this 3 part series I presented an introduction to Kanban. This second part will cover the results obtained by introducing it to an in-flight project and part 3 will give some fuel to the “Physical versus Virtual Kanban boards” debate.

Project Background

This was a service release aiming to investigate and resolve a fixed set of production defects on a newly implemented enterprise scale system. The team consisted of 6 people onshore including Project Manager, Work Packet Manager, Technical Architect, System Analyst and 12 offshore developers (with limited experience of the system). This was a Waterfall project with the project plan based on the agreed prioritized defect list, a fixed resource and time-boxed approach. The number and complex nature of the defect investigations together with dependency management (with other teams) made the tracking of items within the project difficult and opaque which exposed the lack of a structured workflow within the team.

Approach Taken

Mid project I suggested the team adopt a Kanban approach and after explaining the concept to the team quickly got their buy-in. A quick virtual task-board was introduced (in Microsoft Excel initially) with columns defined based on the current informal process with added enforced quality assurance steps. Each work item (defect or change request) was added to the board and tracked, with updates applied daily by the team, as a very minimum, during a morning stand-up.

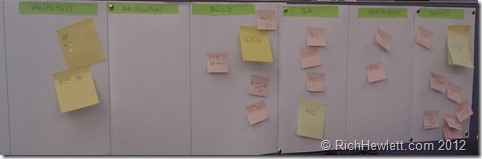

The task-board immediately brought a visual dimension to the project status making managing work in progress (WIP)easier and it also helped to bring focus to the daily stand-ups. After this initial success, to overcome the limitations of the virtual board and to get wider team involvement, the project moved to a physical board with very positive results.

The new board evolved from the previous version based on feedback and was simpler to use. Its physical nature and the fact that it was always on display for the team to consume made a huge difference and resulted in full team commitment to the approach. The physical board became the focal point for the daily stand-ups and for ad-hoc progress updates. The off-shore’s teams updates were applied regularly by the onshore coordinator. Team members used the Kanban queues to action work and move them to the next queue, monitoring/resolving blockages.

What worked well

Implementing Kanban was particularly easy compared to other methods and approaches. As the method logically represents a team to-do list it was easy to explain to people and therefore was not seen as a new complicated process which no doubt aided adoption with the team. It was immediately apparent that this method would compliment and not conflict with existing methodologies and processes. The fact that the board initially should mirror you current processes combined with the fact that it is a method not a methodology meant that it easily slotted in. Again this helped with team adoption and it received a very positive reception from the project team.

The team liked that Kanban immediately brought a visual dimension to project status. They could quickly see items in their queues and where the bottlenecks (if any) were. One quick glance at the board showed the current status of all items. This enabled the team to quickly provide progress updates and set realistic expectations with stakeholders outside the project team. Effort was saved by avoiding wasted deployments into test environments by being able to see at a glance what was going to be ready to deploy in the next build and then set early expectations with the QA team on whether they wanted to take the build or not.

As the flow of work was visualized and monitored it became easier to enforce the current process stages more explicitly. An item would have to pass through the “code review” stage before it could get to the “Ready to Deploy” stage - not only that but the process was completely transparent and clear to everyone involved. This aided communication too which facilitated the current process. As the process was transparent, and the team were able to use the stages as a common ‘vocabulary’, amendments to the process were easily discussed and small incremental process improvements were made, increasing the efficiency of the team. Kanban encourages this constant improvement and the flexibility of the method ensures that it is not a barrier to change.

From a project management perspective the board provided an excellent starting point for meeting updates and status tracking. With all WIP now visible the control of that work, and the resources involved became easier. It was this visibly that actually triggered a useful resource allocation investigation resulting is resources being discovered to be under-utilised in one area and enabled reallocation.

On this project the move from a virtual software task-board (albeit a very simple one) to a physical board made a huge difference and it made the whole method very tangible and “real”. Not just another piece of software to update but something different, something big and bold and in the room!

What didn’t work so well

With any new method a team has to find its feet and test the boundaries of what is productive and what isn’t. The rules to our process and our task board were not as clearly communicated to the whole team as at first thought resulting in some lack of full team ownership and involvement in the first few days. This was evidenced by some of the team acting as purely ‘read-only’ users initially until they were encouraged to fully participate and engage with the method. Despite being a simple concept, without an explanation of the columns their meaning was open to a users interpretation. These were not problems with the Kanban method but merely communication problems that were quickly rectified.

It was discovered that the Kanban board could become misused. There was an urge to overcomplicate the board by adding more detail to the columns and the cards (such as expected delivery date and resource names). As our first board was virtual we found that additional information could easily be added without much control. This was stamped out early on after discussions within the team led to the information that was only required for reporting and tracking reasons being added or supplied from elsewhere as required. The board was simplified again and then a subsequent move over to a physical board helped eradicate this problem.

We found that it was possible for the Kanban board to be used to just display the current status of work as opposed to being used as intended to drive work allocation. The board was being updated daily to reflect the days progress but the board was not driving the workflow and the team was not using the queues to allocate all their work. This meant that it was still adding value as an information radiator but not enabling its full potential. A similar problem was that some WIP items were not added to the board at all but managed separately. This was compounded if stand-ups were driven from an alternative list (defect tracker tool, meeting notes) instead of the Kanban board. All team members had to be reminded that all WIP had to be on the board no matter what the work was was, as it all had to be made visible. Luckily these issues were overcome by reminding people to use the board as the “one truth” and ensuring that all work was progressed via the board, which in a short time became embedded in the team practices.

An area where Kanban (and indeed most Agile methods) suffers is the ‘Remote Team’ scenario. The common assumption that all the teams are co-located is a common failing but one that has to be overcome using practical solutions where possible. Ideally teams need to be co-located for maximum efficiency but the use of telepresence, chat tools and conference calls can help. On this project we managed with an on-shore coordinator acting as a proxy to the offshore team and the Kanban board, combined with usual modern communication methods. Use of a good virtual Kanban board would potentially resolve some of these issues. To be clear Kanban did not introduce any additional impediments to remote teams than didn’t already exist within the team and its methodology.

Summary

This was just an informal trial of Kanban on a inflight project and so in the future I would like to extend the trial to other projects but with some adjustments. At project kick off I would not assume that the whole team had an understanding of the columns and the workflow process, and would ensure full buy-in. More monitoring of ‘cycle time’ would be advised to gain more insight into the current process. I would also like to trial some of the professional virtual task-board software on the market, together with possible integration with Team Foundation Server Work Items.

In summary the Kanban method worked very well on this project and with its simple/flexible approach I’m sure that it can be useful on a huge variety of projects. Critically the feedback from this project team was extremely positive, so much so that team members actually went on to implement Kanban on their other projects afterwards. It was seen by the team (and stakeholders) as a successful work tracking and communication technique, whilst also providing the opportunity to continuously improve. I highly recommend considering trialling Kanban on your future projects, and if you can’t manage to go that far then at least start to think how you can visualize your work in progress.